June 08, 2020

The Story of the Health Warriors Who Made Denver Health What It Is Today

This is the latest in a series of articles reflecting on and celebrating the rich history of 160 years of Denver Health.

Back in the early 1960's, Dr. Samuel Johnson was keenly aware of patients as he walked through the lobby of what was then known as Denver General Hospital (Denver Health today). For many, the journey began with a pre-dawn bus ride, two or three transfers, a long wait to see a doctor, and finally, an expensive taxi ride home.

Dr. Johnson, director of Denver General Hospital's neighborhood health program, knew there had to be a better way to deliver healthcare, something more than episodic and crisis-driven care in which patients were stabilized and sent away only to return in another week or another day. He was part of a growing movement of community health workers who believed health – and sickness – were influenced by poverty, violence, education, the environment and many other factors. The new movement also believed that health care was a right – not a privilege. "We saw health as a social justice phenomenon," said Jim Kent, a close friend of Dr. Johnson's who worked in Denver's early community health centers.

When President Lyndon B. Johnson declared a 'War on Poverty,' Dr. Johnson knew there would be money in the federal legislation for all kinds of programs, including health care. Together with then-Denver Mayor Tom Currigan, he began mapping out a series of health clinics in Denver's low-income neighborhoods that could provide not only primary care services, but also dental care, social services, transportation, daycare and educational assistance.

Denver was the first city in the country to submit a grant application to the federal Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO). But the OEO, which was headed by Sargent Shriver, brother-in-law to slain U.S. President John F. Kennedy, awarded its first grant to a health clinic in the Boston area that was said to have connections to the powerful Kennedy clan.

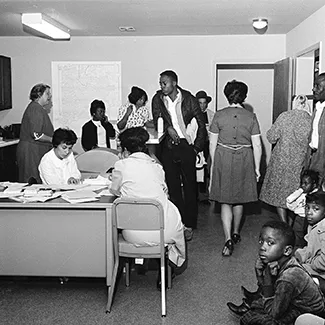

The Birth of Denver's First Community Health Clinic

Undaunted, Denver officials kept working on their grant proposal and on June 30, 1965, they received a grant of $805,000 from the feds and another $89,000 in cash and in-kind services from the city. It was a staggering sum of money at the time. Some of the funds went toward renovating the Macklem Bakery at 529 E. 29th Street in the Five Points neighborhood. The Eastside Neighborhood Health Center (known today as the Bernard F. Gipson, Sr. Eastside Family Health Center) opened on Monday, March 7, 1966. Hundreds of people thronged to the clinic. For many, it was the first time they had ever seen a doctor. The OEO officials administering the huge domestic program knew jobs were key to lifting people out of poverty and insisted that up to 50 percent of the clinic's jobs go to people living in the neighborhood. Residents were hired as medical assistants, X-ray techs, translators, records clerks and pharmacy workers.

Dr. Johnson’s team soon mapped out an ambitious plan for a second health center on the Westside of Denver (known today as Sam Sandos Westside Family Health Center), as well as 12 smaller "health stations" and six maternity and infant care clinics. The OEO didn't want the grant money used on large, brick-and-mortar projects and insisted the health facilities be located in pre-existing buildings. The Westside Health Center was located in a former lumber store; an Eastside health station was in the basement of a church and other health stations were located in low-income housing units around the city.

Turbulence During the Civil Rights Era at Denver Health

The Sixties was a turbulent era in Denver and around the country and nowhere were the waters choppier than in the Neighborhood Health Program. Members of the Black Panthers loitered in the streets, Latino activists from the Crusade for Justice marched through downtown Denver. Board meetings were so heated that some members took to carrying guns. Shortly after midnight on June 28, 1969, a bomb exploded inside the Eastside Health Center. No patients were inside, but a watchman was seriously injured. The case was never solved.

A new facility for Eastside was built a few blocks away at 501 28th Street, which opened in the 1970's. That new facility remains one of the busiest Denver Health clinics. It was recently renovated and became Denver Health's first building fitted with solar panels late last year. Energy and cost savings are expected to be significant for both the environment and for Denver Health.

Expansion of Clinics To Denver Health's School-based Health Centers

Eventually, Dr. Johnson and his disciples departed. But the network of health clinics they had built was durable and continued to grow. In 1987-88, Denver Health partnered with Denver Public Schools to open its first School-based Health Center (SBHC). It was located in Abraham Lincoln High School and the first patient was a student suffering from pink eye.

The School-based Health Centers today reach thousands of kids. Parents no longer have to take a half day off work to take them to doctors' appointments. And kids don't have to lose half a day of school. In addition, the health care workers at the clinics make an effort to enroll the kids and their families in health insurance programs.

Denver Health Family Health Center Expansions and New Partnerships

Over time, Denver Health replaced all of the buildings where its original health centers were located and also began building new health centers (Family Health Centers). Between 2010 and 2019, beautiful, state-of-the art health centers opened in Park Hill, Montbello, Lowry and southwest Denver. The latter facility, called the Federico F. Peña Southwest Family Health Center and Urgent Care, was the last to be completed. The Southwest Family Health Center resembles a small bustling hospital. "It's an enormous clinic and has had a huge impact on our ability to provide care to a larger number of patients," said Dr. Hambidge.

With the completion of the Southwest Peña Family Health Center, Denver Health has turned to smaller projects with community partners. One of those is the Rose Andom Center at 13th Avenue and Fox Street for victims of domestic violence. Another is the beautiful Chanda Center for Health in Lakewood for patients with long-term disabilities from spinal cord injuries. The Chanda Center offers therapies such as acupuncture, massage and yoga, and Denver Health offers traditional medical services at the facility once a week for half a day.

Later this year, the Sloan's Lake Primary Care Center on West Colfax Avenue is expected to open. The Sloan's Lake facility is the result of a three-way partnership between Denver Health, the Denver Housing Authority and St. Anthony's Hospital. The clinic will contain 14 exam rooms and will be located on the first floor of a Denver Housing Authority Assisted Senior Living Facility. "So it'll have a large geriatric focus," said Dr. Hambidge.

But that's not all. A federally qualified health center will also be located in Denver Health's new Outpatient Medical Center (OMC) on Bannock Street. The OMC is a huge addition to the main campus. The 300,000-square-foot building will house many other clinics and services, including an urgent care clinic, numerous specialty clinics for adults, a pharmacy and eight ambulatory operating rooms. Once it opens, Denver Health will have 34 federally qualified health center sites, Dr. Hambidge said.

Read more stories celebrating Denver Health's 160th anniversary.